In March, a BBC interview with Mohamed Irfaan Ali, the President of Guyana, reignited the debate over who should fund climate action. President Ali criticized the “hypocrisy” of Western nations on environmental issues. He highlighted their historical contribution to the current climate crisis and argued that Guyana has been preserving biodiversity since developed countries went through the Industrial Revolution. His comments underscore the ongoing debate over climate finance.

In March, a BBC interview with Mohamed Irfaan Ali, the President of Guyana, reignited the debate over who should fund climate action. President Ali criticized the “hypocrisy” of Western nations on environmental issues. He highlighted their historical contribution to the current climate crisis and argued that Guyana has been preserving biodiversity since developed countries went through the Industrial Revolution. His comments underscore the ongoing debate over climate finance.

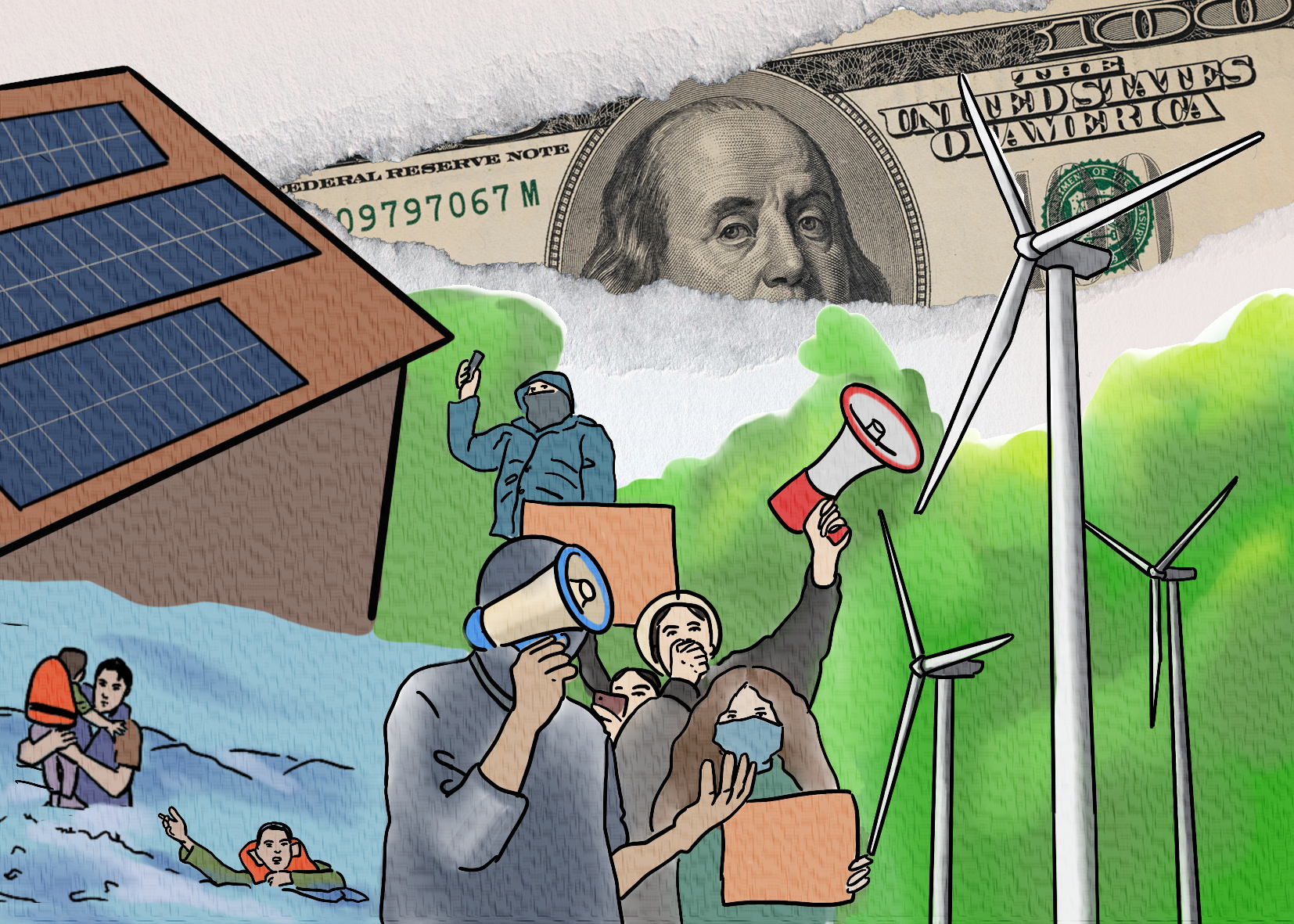

Today, climate finance has become one of the most critical issues in climate action. Despite its significance, the reluctance to bear the costs of climate action fuels this controversy. The SeoulTech has taken a closer look at climate finance and its current context.

Climate finance refers to the financial resources used to mitigate and adapt to climate change. These resources can be mobilized by a wide array of entities, including public, private and alternative third actors from transnational to local scales. Climate finance takes various forms, including grants, concessional and non-concessional loans, technical assistance, bonds, stocks, and risk insurance. Addressing climate change demands more substantial financing, and the lack of investment is a significant barrier to climate action, especially for developing countries. To address this problem, multilateral funds like the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), and the Adaptation Fund (AF) have been set up.

Despite the existence of these multilateral funds, the gap is growing between current investment flows and the target levels needed to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement and UNFCCC. According to the 2023 IPCC report, annual climate investment flows need to increase by three to six times to keep global warming within 1.5°C or 2°C. Various factors, including short-termism, home bias, and a lack of regulatory frameworks, drive this substantial gap.

Insufficient resources can lead to debt distress and environmental maladaptation, especially for developing countries that lack fiscal grounding. This can exacerbate the global outlook on climate action, as the negative impacts of such failures disproportionately affect the vulnerable populations in these countries. The continuous cycle of loss and damage not only pushes them into debt traps but also weakens their competitiveness, extending their fiscal limitations.

Developing countries have grounds to remonstrate with developed countries over the climate action regulations, which address problems primarily caused by the activity of these wealthier nations over the last 50 years. In the UNFCCC, global agreements emphasize the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities” to ensure developed countries meet their obligations. Nonetheless, practical instruments to make them fulfill these responsibilities are lacking.

This year, climate disasters have already been reported in many countries, and Korea is unlikely to be an exception in the upcoming summer. As the climate crisis worsens, it is crucial to focus on raising climate finance so that the pledges of the Paris Agreement and UNFCCC can be met, rather than having abstract debates about what the world should do. It is time to transpose discussions into tangible action.

Reporter,

Kyungmin Shin

Comment 0

Comment 0 Posts containing profanity or personal attacks will be deleted

Posts containing profanity or personal attacks will be deleted